Pampean Short-faced Bear (Arctotherium (Pararctotherium) tarijense)

Fig 1. An artist’s interpretation of Arctotherium tarijense, with guanacos (Lama guanicoe) in the background. Painting used with permission from the artist Hodari Nundu.

Taxonomy

A subject of debated taxonomy, the animal here referred to as Arctotherium tarijense, the Pampean short-faced bear, is considered variously a unique subgenus, Pararctotherium, an entirely separate genus (1), or, in most recent papers, a species of genus Arctotherium (2) (3). Whatever its exact taxonomic distinction, A. tarijense was a bear of the clade Tremarctinae—the short-faced bears. Of this family, only 1 species, the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), survives (11). Other members of the genus Arctotherium included the (probably older) A. bonariense, previously the type of ‘Pararctotherium enectum’, the contemporaneous A. wingei, as well as A. vetustum and A. angustidens (3). While A. wingei was known from the very northernmost parts of the continent, A. tarijense hailed from the southerly regions (2).

Interestingly, genetic evidence indicates that genus Arctotherium is more closely related to the diminutive spectacled bear than to the giant North American short-faced bears, suggesting that the great size of the Arctotheres may be a case of convergent evolution (11).

Distribution

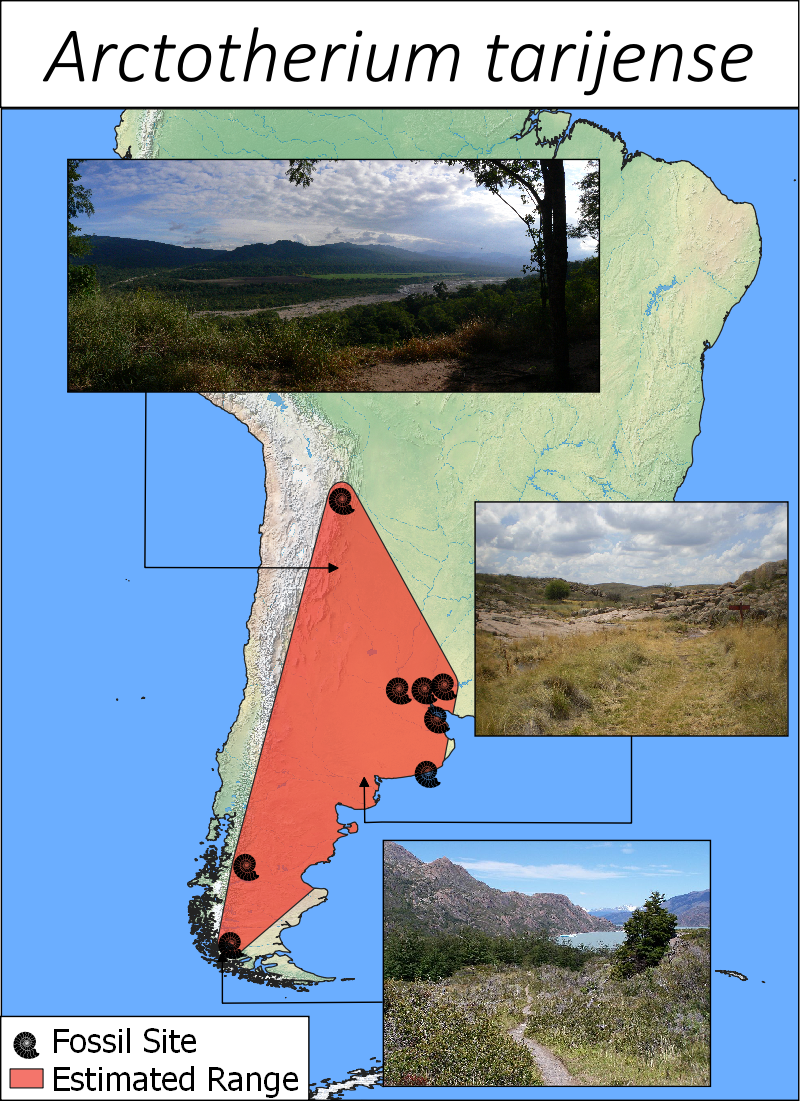

As noted, A. tarijense inhabited the southern reaches of South America, making it the most southerly bear in the world. The most chronologically recent finds, from Cueva de los Chingues in Chile and Río Negro County in Uruguay, both date to around 11,000 BP (2). As with all prehistoric genera, however, the time of last remains cannot necessarily be taken as the exact date of extinction.

The Pampean short-faced bear had a broad but very southerly distribution in the cone of South America. From the south of the Pampean region into Uruguay and Bolivia (2), the species also crossed the Andes, with finds from the Central Patagonian region of Chile (3). Finds from Brazil have typically been assigned to the northern A. wingei (5), but may belong to a fourth species, A. vetustum, known otherwise only from the Middle Pleistocene (2). Either way, they most likely are not A. tarijense. The southernmost remains of A. tarijense stem from the Pali-Aike National Park in the very south of Chile, in the subpolar Magallanes Region (1) (2).

Fig. 2. The estimated range of Arctotherium tarijense, based on fossil sites. Samples of habitats in the region are also included.

Morphology and ecology

Arctotherium tarijense was a very large bear, particularly by modern standards. At an estimated weight of upwards of 400 kg (6), it would have been the size of the very largest modern brown bears (Ursus arctos), and twice the weight of an average European bear (7) (8). Even so, it was still dwarfed by its earlier relative (and probable ancestor), A. angustidens, which at around 1200 kg would have been the largest bear ever known (6). The decrease in size may have been a response to increasing inter-predatory competition, and a shift in diet towards a more omnivorous and/or herbivorous lifestyle, similar to that seen in modern-day brown bears. The degree of competition would have varied from region to region, and it seems plausible that A. tarijense, also like brown bears, would have varied its diet depending on the region. Wear patterns and dental pathologies in fossil teeth indicate omnivory coupled with a substantial consumption of meat (3).

The distribution of the Pampean short-faced bear was one of harsh and often cold environments. In the plains and mountains of southern Patagonia, its main competitors would have been the enigmatic giant Patagonian panther (Panthera onca mesembryna) and the sabretooth Smilodon, as well as the canid Dusicyon avus (1)(3). In the more northerly parts of its range, where it entered the fertile fields and wetlands of Uruguay and the northern Argentine, it would have met a broader range of competitors, including the large canid Protocyon and the cougar (Puma concolor) (9). Herbivores in southern Patagonia included horses of the genus Hippidion, mylodont ground sloths, and guanacos (Lama guanicoe) (1). Also present were camelids of the species ‘Lama gracilis’ (1), which may in fact simply be a now-defunct lowland population of vicuñas (Vicugna vicugna) (10). Further north, in Central Patagonia, the Pampean short-faced bear is also found alongside members of the genus Macrauchenia (3).

The advance of A. tarijense into the most southerly parts of its known distribution must have been comparatively late, between 20,000–18,000 BP. This is because the entirety of southwestern Patagonia, and indeed nearly all of Chile up to the Zona Sur region, was glaciated before then (1) (2). As a denizen of the Southern Cone, the Pampean short-faced bear would have been subject to frequent shifting habitats and range-alterations, the Patagonian plains shifting from xeric shrub to cold grasslands (1), the southern forests growing and retracting. Considerations of the stark, at times subpolar conditions endured by A. tarijense raise another question: that of hibernation. Hibernation in living bears is known only from the genus Ursus, where the trait is widespread. The only living representative of Tremarctinae, the spectacled bear, does not hibernate (13). It is, however, a tropical species, and as such would not be expected to. Indeed, the restriction of hibernation to the genus Ursus may well be an artifact of that genus containing the only surviving bears with cool-temperate or arctic distributions. Even today, the climate of Patagonia is cool and variable, owing to the high latitudes (13)—comparable in fact to the North American Great Lakes region and above. This would only have been more extreme during the Pleistocene (12) (1), with much of the region being glacier-adjacent plains, not uncomparable to the cool flats of Doggerland or the margins of the North American icesheet. Tantalising evidence of potential hibernation-behaviour comes from the discovery of three specimens of the earlier Arctotherium angustidens, found together in a cave and constituting what appears to be a family-unit (13). That the cave should have been a den for food-storage seems unlikely, since the excellent state of the bear-specimens speaks to good preservation-conditions, yet no remains of prey-items were found at the site. The presence, then, of three seemingly related bears in an otherwise empty cave renders hibernation a plausible explanation. Remains referred to other species of Arctotherium, including A. tarijense, have also been found in caves (13)—little evidence in isolation, since these remains were scantier, yet evocative in light of the A. angustidens remains. Ultimately, the presence of hibernation in the Pampean short-faced bear cannot currently be confirmed or denied, but there is evidence enough, both ecological and palaeontological, to elevate the possibility.

Citations

1. Prevosti, F., Soibelzon, L., Prieto, A., Roman, M. and Morello, F. (2003). The southernmost bear: Pararctotherium(Carnivora, Ursidae, Tremarctinae) in the latest Pleistocene of southern Patagonia, Chile. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23(3). 709-712. DOI: 10.1671/0272-4634(2003)023[0709:tsbpcu]2.0.co;2

2. Soibelzon, L., Tonni, E. and Bond, M. (2005). The fossil record of South American short-faced bears (Ursidae, Tremarctinae). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 20(1-2), 105-113. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsames.2005.07.005

3. Mendoza, L. P., Mena, F., Bostelmann, E. (2015). Presence of Arctotherium (Carnivora, Ursidae, Tremarctinae) in a pre-cultural level of Baño Nuevo-1 cave (Central Patagonia, Chile). Estudios Geológicos. 71(2). 41-367. DOI: 10.3989/egeol.42011.357

4. Trajano, E., Ferrarezzi, H. (1994). A fossil bear from northeastern Brazil, with a phylogenetic analysis of the South American extinct Tremarctinae (Ursidae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14 (4),552–561. (17) (PDF) The fossil record of South American short-faced bears (Ursidae, Tremarctinae). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223390695_The_fossil_record_of_South_American_short-faced_bears_Ursidae_Tremarctinae [accessed Jun 18 2021].

5. Trajano, E. and Ferrarezzi, H. (1994). A fossil bear from northeastern Brazil, with a phylogenetic analysis of the South American extinct Tremarctinae (Ursidae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14(4). 552-561.

6. Soibelzon, L. and Schubert, B. (2011). The largest known bear, Arctotherium angustidens, from the early Pleistocene Pampean region of Argentina: with a discussion of size and diet trends in bears. Journal of Paleontology. 85(1) .69-75. DOI: 10.1666/10-037.1

7. Pasitschniak-Arts, M. (1993) Mammalian Species- Ursus arctos. American Society of Mammalogists, Smith College. Archived on 31 March 2017.

8. Swenson, J., Adamič, M., Huber, D. and Stokke, S., 2007. Brown bear body mass and growth in northern and southern Europe. Oecologia, 153(1), pp.37-47. DOI: 10.1007/s00442-007-0715-1

9. Ubilla, M., Corona, A., Rinderknecht, A., Verde, M. (2016). Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3) and Continental Beds from Northern Uruguay (Sopas Formation): Paleontology, Chronology, and Climate. In book: Marine Isotope Stage 3 in Southern South America. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-40000-6_11

10. Weinstock, J., Shapiro, B., Prieto, A., Marín, J., González, B., Gilbert, M. and Willerslev, E., 2009. The Late Pleistocene distribution of vicuñas (Vicugna vicugna) and the “extinction” of the gracile llama (“Lama gracilis”): New molecular data. Quaternary Science Reviews, 28(15-16), pp.1369-1373. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.03.008

11. Mitchell, K., Bray, S., Bover, P., Soibelzon, L., Schubert, B., Prevosti, F., Prieto, A., Martin, F., Austin, J. and Cooper, A. (2016). Ancient mitochondrial DNA reveals convergent evolution of giant short-faced bears (Tremarctinae) in North and South America. Biology Letters. 12(4) .20160062. DOI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4881349/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0062

12. Bendle. J. (2020) Patagonian Ice Sheet at the LGM. AntarcticGlaciers.org. Addressed 19. June 2021. http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/glacial-geology/patagonian-ice-sheet/introduction-patagonian-ice-sheet/

13. Soibelzon, L., Pomi, L., Tonni, E., Rodriguez, S. and Dondas, A. (2009). First report of a South American short-faced bears' den (Arctotherium angustidens): palaeobiological and palaeoecological implications. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 33(3). 211-222. DOI: 10.1080/03115510902844418