Elephants of the Aegean - Dwarfs and Giants of the Ancient Sea

Introduction

As much as we are fascinated by the utterly alien—those creatures, real or imagined, which are so entirely odd as to surpass all frame of reference—there is an equal fascination of the almost-pedestrian. There is something uniquely paradoxical about the words “dwarf elephant”. In a world mostly denuded of large animals, where the biggest creature many people can expect to see in the forest is a somewhat imposing deer, the elephant is the giant of the natural world. The very adjective “elephantine” denotes a thing so large as to be clumsy and ungainly. And yet, though largeness certainly was the rule for elephants, past and present, there must always be the exceptions that prove it. Across the world, islands used to be home to dwarf elephants, from the Channel Islands of California (11) to the wine-dark waters of the Mediterranean (1) (14). In this article, we will be exploring those diminutive specimens which inhabited the rocky outcrops now called the islands of Greece. It is a story confused and complicated by lacking fossils, competing studies and the inevitable mists of time, yet it is a tale worth telling all the same.

The Origins and Relations of the Dwarf Elephants

In discussing the relationships of the various Aegean dwarf elephants, it must first be clarified that we are not talking about one species, spread across an archipelagian distribution. Rather, they were a complex of related animals, most of whom likely had their origin in a shared initial dispersal-event (1). The dwarf elephants of the eastern Mediterranean are not nearly as well-studied as those from the west, and only Crete had named species until recently (4). However, since 2013, species have been named from Tilos and the Cyclades, while material from a range of islands has been identified as belonging to the mainland straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus (3) (14). Nevertheless, remains from many islands are still undetermined (14). The species range substantially in size, from the remarkably diminutive Mammuthus criticus of Early Pleistocene Crete, with a predicted weight of only some 300 kilos, to the much larger Palaeoloxodon chaniensis, also from Crete, estimated to be only 20% smaller than the (presumably ancestral) P. antiquus (1).

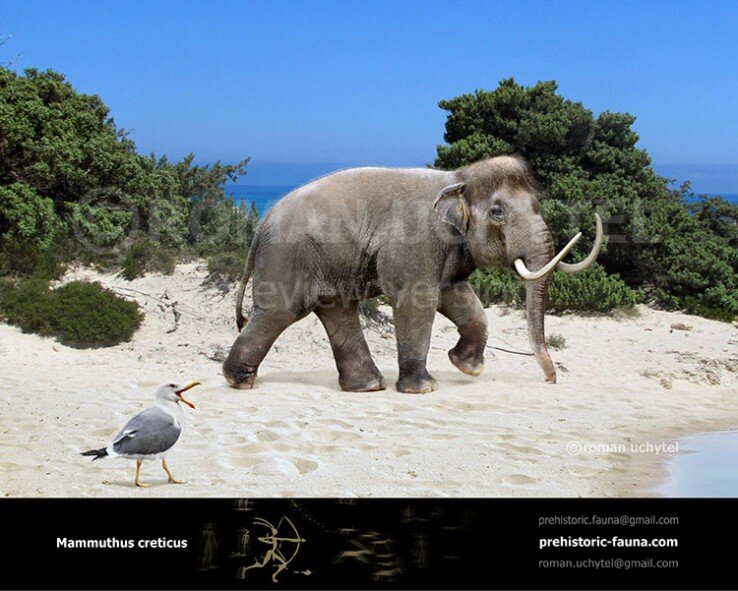

The taxonomic situation is most complicated on Crete, where three species of elephant are known from the Pleistocene—the aforementioned M. criticus and P. chaniensis, as well as a third, P. creutzburgi (4) (1) (6). Of these species, M. criticus, the Cretan dwarf mammoth, is the oldest. A fairly substantial debate has taken place regarding the taxonomic affinities of this animal. Originally classified as Elephas criticus (7), this view was challenged by molecular studies. In a paper analysing the 43 bp sequence of the cytochrome b gene, extracted from an 800k-year-old fossil, the species was reclassified as a mammoth. A further wrinkle was thrown into this story when the sequence-based study in turn was shown to be faulty (8), yet even more recent morphological evidence has nevertheless supported the mammoth-classification, and its status as M. criticus now seems fairly confident (9).

Fig 1. Cretan dwarf mammoth (Mammuthus creticus). Art by Roman Uchytel, used with permission.

Whatever the species’ affinities, its origins seem to lie around the dawn of the Pleistocene. Its date of extinction appears to be around the early Middle Pleistocene, potentially corresponding to the warm period known in Alpine geology as the Günz-Mindel interglacial, (0.75–1.0 Ma) (1). At this time, exceptionally high sea-levels may have divided Crete into a series of smaller, isolated isles—conditions which the dwarf mammoth evidently could not endure. At any rate, its extinction paved the way for the arrival of the more recent species of Cretan elephants. A few words must be given to their taxonomy, as it too is debated. P. creutzburgi is by far the better known of the two species, represented by remains from at least 22 localities (10) (1). At an estimated bodyweight of circa 3000 kg, it was 50% the size of the mainland straight-tusked elephants—far larger than M. criticus, (3) but smaller than the third species, the contemporaneous P. chaniensis (1). As mentioned prior, the latter species is thought to have reached 80% the size of the mainland taxa, making it hardly a “dwarf” at all. The fragmentary nature of its remains, however, combined with the lack of more recent fossil surveys, makes it difficult to determine whether creutzburgi and chaniensis truly are distinct taxa, or whether the latter represents oversized individuals of the former. It is perhaps possible that what is being observed is a case of repeated colonisation events, not unlike that postulated for the US Channel Islands (11). In that scenario, the larger species would represent more recent arrivals from the mainland, whilst the creutzburgi animals stem from an earlier dispersal. Crete, however, is substantially more isolated than the Channel Islands, which may speak against this hypothesis. At any rate, in what appears to be the latest word, Sen, S. (2017) edges towards regarding them as distinct.

As for the remaining islands, our picture is still somewhat fragmentary. The reader may refer to the map in the “Distribution” section below. Numerous islands were host to elephants, and though some were totally endemic species, others have been assigned to P. antiquus—populations, presumably, that had not yet had enough time to fully speciate (14). The Dodecanese in particular appear to have been a hot-spot for endemism, with Tilos hosting the named species, Palaeoloxodon tiliensis (2), whilst Rhodes and Astypálaia likewise hosted as-yet unnamed endemics (14). Another relatively new taxa, Palaeoloxodon lomolinoi, was named from the isle of Naxos in 2014 (15). Whilst the latter species is only officially known from Naxos, this island, alongside Delos and Paros, were all united into one Palaeo-Cycladic isle of almost 10,000 square kilometres until the Last Glacial Maximum, making it overwhelmingly likely that the unassigned elephants from here are all conspecific (14) (15).

The Aegean islands appear to have been populated in at least two separate dispersal events. The first, which may have occurred sometime around the Plio-Pleistocene boundary (circa 2.5 Ma), gave rise to Mammuthus criticus (9) and, presumably, a host of other insular mammoths of which we have no remains. The Pleistocene saw a turnover of this earlier mammoth-fauna to one dominated by elephants of the aforementioned genus Palaeoloxodon, the straight-tusked elephants (1) (9). This second wave of dispersal seems to have taken place about 200kya at the earliest (1), at a time when mammoths were no longer present in the mainland surrounding the Aegean. Most likely there was not merely one colonisation event, though clusters of islands may have been populated in single movements. The Cyclades, for instance, seem to be an instance of the latter. A 2019 review of the data found that the species inhabiting the palaeo-Cycladic island all form endemic species, whereas those inhabiting the isles of Cephalonia, Kalymnos and Kythera all belong, at least at a species level, to the mainland P. antiquus (14).

Distribution

Elephants were widely distributed in the Aegean, right up until the cusp of historical times (2) (1). Of the Aegean isles, elephants are known from Crete, Astypalea, Cephalonia, Dilos, Kalymnos, Kassos, Kos, Kythera, Kythnos, Milos, Naxos, Paros, Rhodes, Tilos and Serifos (1) (14). As noted prior, these were not all members of the same species, but belonging as they all do to the genus Palaeoloxodon, and descending most likely from a shared ancestor, they may be regarded as related populations in varying degrees of speciation. The known distribution of elephants in the Aegean spans essentially the entire sea, with no clear geographic trends. Only from the North Aegean isles are elephants not known, but given the scant records and poor preservation-conditions even on the islands where they are confirmed, this need not be evidence of absence. Also the islands of Euboea and Lesbos harboured elephants during the Pleistocene, but these landmasses were connected to the mainland at the time, wherefore the species inhabited them cannot be considered “island elephants” (14).

Fig 2. Known distribution of Aegean elephants. Data from Sen, S. (2017) and Athanassiou, A., van der Geer, A. and Lyras, G. (2019)

Habitat and Ecology

Ecological constraints—food, water, space—rather than time isolated appear to be the main contributors to insular dwarfism in proboscideans across the board (12), a pattern the Aegean reinforces. The largest by a sizeable margin would appear to be those on Crete—by far the largest of the islands studied, whilst the species on Tilos, Naxos and Rhodes have undergone far more substantial dwarfism (15). That P. lomolinoi—the Naxos taxa—has undergone just as severe dwarfing as the animals from the Dodecanese may seem surprising in light of the previously discussed Palaeo-Cycladic island. This landmass, however, was not in continuous existence (15), and the small stature of the Cyclades-taxa may therefore be explained as a necessary adaptation to the periods during which most of the islands were submerged.

A few words may briefly be said regarding the various taxa, though our scant remains allow only glimpses. The Cretan elephants were as noted by far the largest, with even the smaller of the two proposed taxa, P. creutzburgi, having an estimated weight of 3 tons and a shoulder-height of 3,7 metres (1) (19). They had straight or gently curved tusks, like the mainland straight-tusked elephants, and likewise similar dentition. A question that has caused quite a lot of consternation is why, exactly, the Cretan elephants did not undergo pronounced dwarfism, unlike both the other Aegean elephants and their own predecessor on Crete, the Cretan dwarf mammoth (18) (19). The strongest explanation at presence is the presence of a broad radiation of endemic deer on Late Pleistocene Crete, unlike the earlier Pleistocene and other Aegean islands, but similar to Sardinia, where the endemic proboscideans likewise underwent only limited dwarfing (18).

On the opposite end of the spectrum, plausibly the smallest elephant from the end-Pleistocene Aegean was the Tilos elephant, though still larger than the earlier Mammuthus criticus (1). About 50% the median size of continental P. antiquus, with a shoulder-height of 180-190 cm (2) and an estimated body-mass of 630-831 kg (3). Compared to related taxa, its limbs were relatively slender, evidently adapted for life on rugged, mountainous Tilos (1). Last of the named taxa is Palaeoloxodon lomolinoi, the Cycladic dwarf elephant, which at only 10% the body-mass of their mainland ancestors may even have been smaller than their Tilos cousins (15).

As regards diet, it is difficult to say much with certainty. The ancestral P. antiquus appears to have exhibited a high degree of dietary plasticity, indicating a degree of adaptability that would likely have been very useful in constrained island-habitats (15) (16). The trend in straight-tusked elephants over the course of the Pleistocene was from a grazing-dominated diet to a more browsing diet by the Late Pleistocene—a development which may have carried over into the insular populations if they descended from this meta-population (15). The ecological context of the various species depended on the islands. Across the Aegean, a commonality was the lack of large predators—likely an important factor in enabling the development towards small body-sizes. By far the most ecologically complex of the islands was Crete, largest and oldest of the archipelago (1) (17)(18). During the Early-to-Middle Pleistocene, the most notable members of the island’s fauna were the aforementioned Cretan dwarf mammoth and the Cretan dwarf hippopotamus. A major turnover of the island’s fauna occurred in the late-Middle Pleistocene, after which developed a new fauna—the one inhabited by the last Cretan elephants, P. creutzburgi and (if not synonymous) chaniensis. Alongside these arrived also the ancestor Cretan deer, Candiacervus, which remarkably radiated into 8 species in only half a million years (17) (19). Other species include the large, terrestrial and long-legged owl Athene cretensis (20), as well as the unusually terrestrial Cretan otter, Lutrogale cretensis, and the diminutive Cretan shrew, Crocidura zimmermanni, the latter of which still endures till today as the last remnant of Crete’s native fauna (19).

The fauna of the remaining islands is more difficult to ascertain. The Cyclades were home also to large rock mice (Apodemus cf. mystacinus) and shrews (Crocidura sp.). This seems an oddly impoverished fauna for so comparatively large an island and may well be an artifact of the region’s exceedingly poor preservation-conditions. The Palaeo-Cycladic island would have represented a far more varied and geographically diverse habitat than the rocky islets today, with large flat plains between the raised hinterlands, practically unknown from the Aegean isles today (15).

Fig 3. The isle of Tilos in the Dodecanese. Small and mountainous, it nevertheless held its own species of elephant for many thousands of years.

Terms of use: This image is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. The image is attributed to Chrischerf and is unedited.

The End of the Elephants

The last vanishing of a species is never an easy thing to pinpoint. The vanishing of a dozen is even harder. When, exactly, did the last elephant disappear from the Aegean? And why? It would perhaps be most convenient to take the questions one at a time, but in this case, the topics cannot be disentangled. Unfortunately, nowhere does the previously discussed scarcity of the fossil record pose a larger issue than on this topic. We may start with Crete. Here as elsewhere, the evidence is unfortunately very poor. Regarding elephant remains, a femur dated to circa 49,000 BP is the only material with any confident dating, though remains of P. creutzburgi are generally correlated as Late Pleistocene (1). Looking at other Cretan taxa is little help, as the most recent dated remains of the deer Candiacervus are from 21,500 BC, but again, the animals are known only from scattered material (17). There is some, tentative evidence that Crete may have been colonised by humans already 120-75 thousand years ago (18), though if so, this could not yet be by Homo Sapiens. Certainly, the native Cretan fauna was gone by the dawn of the Neolithic (circa 7000 BC) and before Minoan times (19). A human explanation seems intuitive, plausibly coinciding with the same colonisation event that brought over the ancestors of the Cretan ibex (Capra aegagrus cretica), but in lieu of any confident archaeological evidence, we can but speculate (19).

The Naxos elephants were still present in the Late Pleistocene (15), but again, scanty remains make dating the extinction impossible. At this point, comparison with other parts of the Mediterranean may be elucidating. Unfortunately, poor remains and blurred stratigraphy are the norm for the entirety of the sea, yet some clues do appear. On nearby Cyprus, the native dwarf elephant, P. cypriotes, seems confidently to have ranged into the early Holocene, alongside the remainder of the isle’s sparse, endemic fauna (21). On Sardinia, proboscidean-remains themselves are exceedingly poor, yet the decline of the general fauna to which they pertained can nevertheless be connected with reasonable certainty to human settlement (22). Indeed, returning to the Aegean, there is one isle on which we have confident datings, not merely to the Holocene, but to the very brink of history—Tilos. Here, the dwarf elephants seem to have survived until only about 4000 years ago (2) (23). This judgement is based on the dating of two separate remains, pinned respectively to 7090+/- 680 and 4390 +/- 600 BP.

This significance of this last dating seems very underappreciated in the literature. Large amounts of pages, essays and articles have been devoted to the subject of possible historical references to dwarf elephants—from their skulls allegedly inspiring stories of cyclopses, to being traded as gifts to Egyptian pharaohs (23). Nevertheless, bar Masseti, M. (2002), written nearly 2 decades prior to the writing of this article, precious little discussion has connected the supposed historical sources with the actual fossil-evidence of late survival. If these datings from Tilos are accurate, several implications follow. The first concerns the apparent extinction-dates of other insular taxa: Tilos neither is nor was the largest or the most fertile of the islands that hosted elephants. The sparsity of our data being as it is, it is entirely conceivable—though at present equally unproveable—that elephants from at least some of the other Aegean isles survived until comparatively recent times. The second implication is just as significant if not more: A date of 4000 BP places the last records of P. tiliensis well within the height of Minoan civilisation. Even the older of the two fossils, if closer to 6500ky in age, only predates the rise of the Minoans by about a millennium. It is therefore entirely plausible—almost certain, in fact, given the thalassocratic dominance of the Minoans—that the ancient Cretans and their neighbours would have been aware of the Tilos elephants. This being within the window of recorded history, the question obviously follows: is there any historical evidence?

The answer there, it may be said straightforward, is “perhaps”. We have in fact already touched on one piece of putative evidence—a wall-painting, in the tomb of Rekhmire in Egypt, portraying a small elephant, being bestowed by Syrian tributaries (23). Much has been made of this painting, and it has repeatedly been claimed to represent a pygmy elephant. Evidence in favour of this includes, obviously, the small stature of the elephant as portrayed, as well as the apparently well-developed tusks, indicating an adult animal. Against this has been raised the objection that the small size of the elephant may well be a mere stylistic device, not uncommon in Egyptian art (23). However, on the same painting, a giraffe is portrayed in natural size relative to the humans, while a bearer carries tusks apparently far larger than those of the diminutive elephant. This seems reasonable, albeit not conclusive, evidence that the elephant is not a stylised adult. There remains, however, another explanation: What we are seeing is a juvenile. As noted above, the size of the animal’s tusks is inaccurate for an infant elephant, but here it may simply be countered that merely because the size of the animal is not stylised does not mean all features of it are photorealistic. Furthermore, the elephant on the Rekhmire tomb would appear to be covered in short brown fur—characteristic of juvenile elephants, but not found in adults. In summary, it seems to the present author most likely that the animal on the Rekhmire tomb is neither a pygmy elephant, nor an artistically shrunken adult, but rather an infant, stylistically portrayed with the species’ characteristic tusks, but accurately rendered with fuzzy integument.

Fig 4. The elephant on the tomb of Rekhmire. Often suggested to be a pygmy elephant, the plausibility of this has been questioned.

Terms of use: This image is in the public domain.

Is this, then, the full extent of our supposed historical evidence? Not quite. Lafrenz, K. A. (2004) describes another scene, also from the tomb of Rekhmire, portraying four groups of people bringing tusks to the Egyptians—Nubians, Syrians, men of Punt (debated: possibly the Horn of Africa) and the “Keftiu”. The former three peoples all hail from regions with readily available ivory, both from hippos and elephants (Syria being at the time inhabited by elephants). It is the latter, the “Keftiu”, that are our focus here. They are traditionally interpreted as Cretans. Lafrenz notes in her study that the Cretans alone of the four had no native source of ivory—almost certainly true for Crete itself, but not, it seems, for the Aegean as a whole. Once more, caution must prevail, and it must be noted that there are other possible explanations as well. The Minoans were a people of mariners and traders. It is not at all unfeasible that they could have simply purchased ivory from some other region. And yet, the very fact of them being mariners, in the Aegean, at a time when at least one island still seems to have held dwarf elephants—it is certainly intriguing. Doubtless, the barren isle of Tilos could never have supported a large population of elephants, and they would have sustained little exploitation. This may be a strike against the idea that Tilos was a source of ivory, but it may also congrue with the evidence. The most recent bones are dated to 4000 BP, no earlier than Minoan times, but also no later. A more recent survival would increasingly demand the presence of written evidence, heavily implying an extinction-date during Minoan times. If so, the active exploitation of the remaining Aegean elephants in Minoan times for ivory-exports could readily be posited as one (albeit entirely speculative) explanation for their ultimate vanishing.

Conclusions

The story of the pygmy elephants of the Aegean is an unusual one. Short, in geological time, it began with the growing of the first glaciers and the falling of the seas, and ended only a scarce few millennia ago, with the ice once again retreating, and the coming of a new hunter. When, precisely, the last elephants vanished, and their trumpet-calls ceased forever, we will likely never know. Yet what records we do have, scattered though they be, trace a fascinating story of parallel evolution, of island-hopping and drowned lands, and of species growing apart and coming together. In many ways, the ancient Aegean was a laboratory of evolution, each island its own microcosm. Many studies have been done already on the peculiar conditions of the island elephants, but yet more are needed. The end of their story, in particular, is no less fascinating than the beginning, though perhaps rather more melancholy. Did ancient galleys bear dwarf elephants across the sea? Was Minoan ivory harvested, not from the cedar woods of Syria or the hills of Tunisia, but from their own Aegean world? At present, we cannot say, but we can speculate, and implore. Here is a box of mysteries, its answers bound to interest. We need only for talented researchers to dig in.

Citations

1. Sen, S. (2017). A review of the Pleistocene dwarfed elephants from the Aegean islands, and their paleogeographic context. Fossil Imprint. 73(1-2). 76-92. DOI: 10.2478/if-2017-0004

2. Theodorou, G., Symeonidis, N., Stathopoulou, E. (2007). Elephas tiliensis n. sp. from Tilos island (Dodecanese, Greece). Department of Historical geology and Palaeontology. 19-32.

3. Lomolino, M., van der Geer, A., Lyras, G., Palombo, M., Sax, D. and Rozzi, R. (2013). Of mice and mammoths: generality and antiquity of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 40(8). 1427-1439. DOI: 10.1111/jbi.12096

4. Sen, S., Barrier, E. and Crété, X. (2014). Late Pleistocene Dwarf Elephants from the Aegean Islands of Kassos and Dilos, Greece. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 51(1-2). 27-42. DOI: 10.5735/086.051.0204

5. Dermitzakis, M. D. & De Vos, J. (1987). Faunal succession and the evolution of mammals in Crete during the Pleistocene. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 173. 377-408.

6. Kuss, S. E. (1965). Eine Pleistozäne Säugetierfauna der Insel Kreta. Berichte der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft zu Freiburg im Breisgau. 55. 271–348 (15)

7. Poulakakis, N, Theodorou, G. E., Zouros, E., Mylonas, M. J. (2002). Molecular phylogeny of the extinct pleistocene dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus falconeri from Tilos Island, Dodekanisa, Greece. Mol Evol. 55(3). 364-74. DOI: 10.1007/s00239-002-2337-x

8. Orlando, L., Pagés, M., Calvignac, S., Hughes, S. and Hänni, C. (2006). Does the 43 bp sequence from an 800 000 year old Cretan dwarf elephantid really rewrite the textbook on mammoths?. Biology Letters, 3(1). 58-60. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0536

9. Herridge, V. and Lister, A. (2012). Extreme insular dwarfism evolved in a mammoth. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1741). 3193-3200. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0671

10. Poulakakis, N., Mylonas, M., Lymberakis, P., Fassoulas, C. (2002). Origin and taxonomy of the fossil elephants of the island of Crete (Greece): problems and perspectives. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 186. 1-2, 163-183. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(02)00451-0

11. Agenbroad, L., (2012). Giants and pygmies: Mammoths of Santa Rosa Island, California (USA). Quaternary International. 255. 2-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2011.03.044

12. Geer, A., Bergh, G., Lyras, G., Prasetyo, U., Due, R., Setiyabudi, E. and Drinia, H. (2016). The effect of area and isolation on insular dwarf proboscideans. Journal of Biogeography. 43(8). 1656-1666. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12743

13. Athanassiou, A., van der Geer, A. and Lyras, G. (2019). Pleistocene insular Proboscidea of the Eastern Mediterranean: A review and update. Quaternary Science Reviews. 218. 306-321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.028

14. Athanassiou, A., van der Geer, A. and Lyras, G. (2019). Pleistocene insular Proboscidea of the Eastern Mediterranean: A review and update. Quaternary Science Reviews. 218. 306-321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.028

15. van der Geer, A., Lyras, G., van den Hoek Ostende, L., de Vos, J. and Drinia, H. (2014). A dwarf elephant and a rock mouse on Naxos (Cyclades, Greece) with a revision of the palaeozoogeography of the Cycladic Islands (Greece) during the Pleistocene. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology- 404. 133-144. DOI:10.1016/J.PALAEO.2014.04.003

16. Palombo, M. R.M Filippi, M.L., Iacumin, P., Longinelli, A., Barbieri, M., Maras A. (2005). Coupling tooth Microwear and stable isotope analysis for palaeodiet reconstruction: the case study of Late Middle Pleistocene Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus teeth from Central Italy (Rome area). Quat. Int. 126–128. 153-170. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.020

17. van der Geer, A., de Vos, J., Lyras, G., Dermitzakis, M. (2006). New data on the Pleistocene Cretan deer Candiacervus sp. II (Cervinae, Mammalia). Cour. Forscht.-Inst. 256. 131-137.

18. van der Geer. A., Lyras, G., de Vos J., Dermitzakis, M. (2010). Evolution of Island Mammals: Adaptation and Extinction of Placental Mammals on Islands. Blackwell Publishing. 49-61. DOI: 10.1002/9781444323986

19. van der Geer, A., Dermitzakis, M., de Vos, J. (2006). Crete before the Cretans: The reign of dwarfs. Alpha Omega Alpha. 13. 121-132.

20. Pavia, M. & Mourer-Chauviré, C. (2002). An overview of the genus Athene in the Pleistocene of the Mediterranean islands, with the description of Athene trinacriae n. sp. (Aves: Strigidae). Department of Earth Sciences.

21. Athanassiou, A., Herridge, V., Reese, D., Iliopoulos, G., Roussiakis, S., Mitsopoulou, V., Tsiolakis, E. and Theodorou, G. (2015). Cranial evidence for the presence of a second endemic elephant species on Cyprus. Quaternary International. 379. 47-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.05.065

22. Palombo, M. R. (2009). Biochronology, paleobiogeography and faunal turnover in western Mediterranean Cenozoic mammals. Integrative Zoology. 4. 367-386. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2009.00174.x

23. Masseti, M. (2002). Did endemic dwarf elephants survive on Mediterranean islands up to protohistorical times? Department of Animal Biology and Genetics.

24. Lafrenz, K. A. (2004). Tracing the Source of the Elephant and Hippopotamus Ivory from the 14th Century B.C. Uluburun Shipwreck: The Archaeological, Historical, and Isotopic Evidence. Scholar Commons.