Notiomastodon platensis

fig 1. A bull Notiomastodon stands in the sunrise by the Tepui Kukenán in Venezuela, some time in the Pleistocene or early Holocene. Painting used with permission by the author Dhruv Franklin

Taxonomy

The taxonomic history of South American gomphotheres, Notiomastodon among them, is both long, complicated and confusing. Initial specimens, uncovered in the early 19th century, were mostly assigned to various species of Mastodon. This yielded a Mastodon andium from Ecuadorian remains, a Mastodon humboldtii from Chile, and a Mastotherium hyodon from the same region, which, if valid, would have taxonomic precedence over M. humboldtii, and a “Mastodon brasiliensis Lund” from Brazil (3). However, all of these taxa were named on the basis of relatively indeterminate teeth and could not easily be either assigned or delineated from each other. Later studies as the century progressed did not help, yielding Stegomastodon brasiliensis on the basis of the remains previously identified, but not officially named, as “M. brasiliensis”. This new “Stegomastodon”, however, was itself antedated by various other proposed names, and the whole situation was only confused with the entry of self-taught palaeontologist Florentino Ameghino. He named, on the basis of remains primarily form Argentina, not less than 7 new species of Mastodon, based on skeletal material of various sizes, tusk-features and molar morphologies. This confusion did not end in the early 20th century, when several of the Mastodon species proposed by Ameghino were synonymised with older proposals of Stegomastodon taxa, among them one S. platensis. The South American species of ‘Stegomastodon’ possessed major morphological differences from North American taxa, and in 1924 the species and genus Notiomastodon ornatus was erected as a South American-endemic lineage.

Not all authors agreed with these decisions, however, and several retained Stegomastodon in South America, founding within it the sub-genus Haplomastodon. By the 1950s, the number of proposed genera and sub-genera floating in the literature had ballooned to include Cuvieronius, Notiomastodon, Haplomastodon, Aleamastodon and Stegomastodon. It was not until the 2000s that the situation finally began to be reduced and resolved. Haplomastodon was declared a nomen dubium, the remains from “Stegomastodon” referred to Notiomastodon, and the conclusion reached—now the consensus—that there were in Late Pleistocene South America only two taxa of Gomphotheres, the predominantly lowland species Notiomastodon platensis, and the upland species Cuvieronius hyodon (3).

Distribution

N. platensis had an exceedingly wide distribution, spanning the continent of South America. Remains identified with the species are known from every country on the continent save Guyana and Suriname, though its occurrence was not evenly dispersed throughout these regions (1) (2). The species was associated primarily with dry, open habitats, and does not seem to have frequented the interior rainforest. The Uruguayan and Chaco savannas appear to have been core areas of habitat, as was the Atlantic northeast of Brazil, where conditions similar to today’s caatinga scrubland seem to have dominated even during the Pleistocene (1). Its distribution also spanned the Andes, with Notiomastodon inhabiting a broad swathe of the Chilean Pacific coast. The most notable gaps in its distribution occur in the northwest, in Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. Though known locally from all three of these countries, the range of N. platensis here encountered that of Cuvieronius—encountered but did not overlap. Though known from the same regions in all three of these countries, they have never been found at the same localities, almost certainly evidencing a degree of competitive exclusion (3).

Having discussed the geographical distribution of the species, some words may be dedicated to its temporal range. Despite being frequently referred to as a member of the ‘Pleistocene megafauna’, Notiomastodon, alongside a host of other South American taxa, did in fact survive well into the Holocene. Remains have been confidently dated to less than 8.8kya years ago (4), with some estimates predicting an extinction as recently as 6kya (1). Tracing the rear limits of the temporal range is more difficult—though proboscidean remains in South America occur as far back as 2.5 ma, these cannot be identified to the genus or species-level. The oldest definitive evidence of N. platensis is from South Brazil, dating to the Middle Pleistocene (1). That its entrance into the continent was a separate event from that of Cuvieronius seems likely, but which is older cannot be deduced (3).

Fig. 2. The estimated range of Notiomastodon platensis based on fossil sites. Based upon data from PaleoDB (11).

Morphology and Ecology

Notiomastodon platensis was a very large and sturdily built animal, as is characteristic of gomphotheres. The estimated size of the most impressive bulls would have been upwards of 6.5 tonnes, with a height of some 2.8 metres at the shoulders—similar in weight, then, to a large African elephant, whilst noticeably shorter (5). Their skulls were characterised by pronounced foreheads, and their tusks were long and straight, unlike the twisted shape found in Cuvieronius (3). Unlike older species of gomphotheres, as well as juvenile members of Cuvieronius, N. platensis possessed only a single pair of upper tusks, as is seen in extant elephants. The diet of Notiomastodon has been reconstructed based on dental wear-patterns and plant microfossils from fossil teeth. It appears to have been a very generalist animal, consuming both woody stems, leaves and grasses (6). It was capable of shifting its diet across both its temporal and geographical range, depending on the available foods. During warmer periods, and at lower latitudes, animals appear to have fed mostly on C4-grasses and in places mixed vegetation. In the colder reaches of Pleistocene Uruguay, however, its diet shifted entirely to consist instead of C3-vegetation (6). This speaks to a great degree of ecological adaptability, doubtless the reason for its broad geographical range. As noted previously, the species seems to have shown a preference for generally open habitat with dry conditions. This was not, however, a strong specialisation, and remains of Notiomastodon are known in some instances from both wetland and densely wooded locations (3) (1).

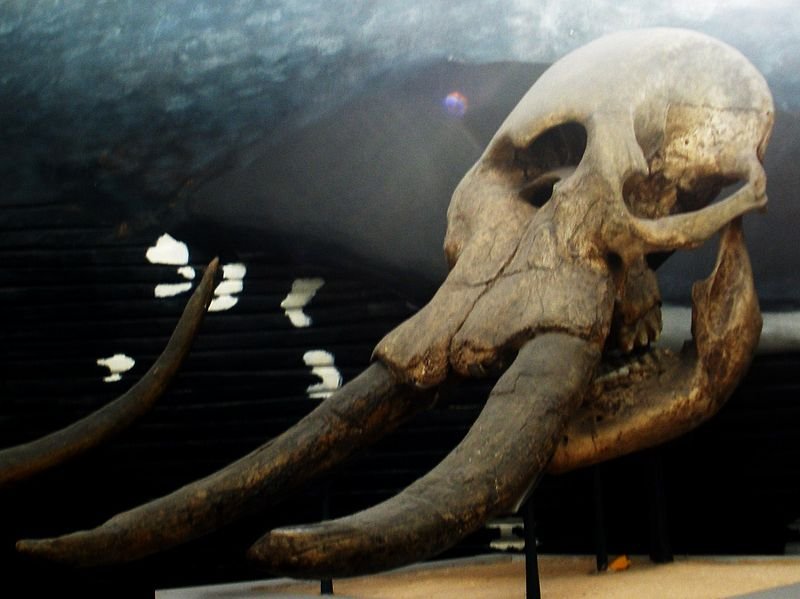

Fig 3. The skull of Notiomastodon (“Stegomastodon”) platensis in the Natural History Museum of London.

Terms of use: This image is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. The image is attributed to Ghedoghedo and is unedited.

The population-structure of N. platensis has been estimated to resemble that of present-day African elephants, with mixed groups of both young and old individuals, representing a variety of age-classes (7). The population from which the latter was deduced, discovered at the site of Águas de Araxá in Brazil, also evidenced an unusually low percentage of juveniles. This could perhaps be the consequence of a drought killing the herd just prior to the beginning of the reproductive season, when the number of present juveniles would have been at its lowest, or the sign of a population either in decline or the early stages of recovery. It might also, however, be indication of a high predation-pressure on young Notiomastodons. Inhabiting a wide range exceptionally rich in other species of megafauna, the gomphotheres would have encountered a host of predators, among them the sabertoothed cat Smilodon populator, the jackal-sized canid Dusicyon avus and its substantially larger relative Protocyon troglodites (8). Still present throughout the continent are jaguars (Panthera onca) and cougars (Puma concolor) (9) 10), both doubtless potential predators of young Notiomastodon-calves. Of other herbivores, the gomphotheres would have shared their range with other now-extinct taxa such as the large toxodont Toxodon platensis, the ground-sloths Megatherium americanum and Eremotherium laurillardi and the deer of genus Morenelaphus and Antifer (8).

Citations

Dantas, M., Xavier, M., França, L., Cozzuol, M., Ribeiro, A., Figueiredo, A., Kinoshita, A. and Baffa, O. (2013). A review of the time scale and potential geographic distribution of Notiomastodon platensis (Ameghino, 1888) in the late Pleistocene of South America. Quaternary International. 317. 73-79. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.06.031

Mothé, D., Aguanta, W., Belatto, S. and Avilla, L. (2017). First record of Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from Bolívia. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 20(1). 149-152. DOI: 10.4072/rbp.2017.1.12

Mothé, D., dos Santos Avilla, L., Asevedo, L., Borges-Silva, L., Rosas, M., Labarca-Encina, R., Souberlich, R., Soibelzon, E., Roman-Carrion, J., Ríos, S., Rincon, A., de Oliveira, G. and Lopes, R. (2016). Sixty years after ‘The mastodonts of Brazil’: The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae). Quaternary International. 443. 52-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.028

Turvey, S. T. (2009). Holocene Extinctions. Oxford University Press. 27-30.

Larramendi, A. (2016). Shoulder height, body mass, and shape of proboscideans. . Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (3). 537–574

Asevedo, L., Winck, G., Mothé, D. and Avilla, L. (2012). Ancient diet of the Pleistocene gomphothere Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) from lowland mid-latitudes of South America: Stereomicrowear and tooth calculus analyses combined. Quaternary International. 255. 42-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2011.08.037

Mothé, D., Avilla, L. and Winck, G. (2010). Population structure of the gomphothere Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82(4). DOI: 10.1590/s0001-37652010000400020

Lopes, R., Dillenburg, S., Savian, J. and Pereira, J. (2021). The Santa Vitória Alloformation: an update on a Pleistocene fossil-rich unit in Southern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Geology. 51(1). DOI: 10.1590/2317-4889202120200065

Quigley, H., Foster, R., Petracca, L., Payan, E., Salom, R. & Harmsen, B. 2017. Panthera onca (errata version published in 2018). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T15953A123791436. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en

Nielsen, C., Thompson, D., Kelly, M. & Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. 2015. Puma concolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T18868A97216466. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T18868A50663436.en

Palaeobiology Database. (2021). Notiomastodon platensis. https://paleobiodb.org